Chair's March Blog: Time, Love, Courtesy, Promise and Place

Time, Love, Courtesy, Promise and Place - Ingredients for a Slow Rise Eucharist

By Anne Dixon

For ever, I shall root you in the wood,

under the sun shall bake you bread

of beechmast, never let you forth

to the white desert, to the starving sand.

But we shall sit and speak around

One table, share one food, one earth.

Excerpt from ‘Rublev, by Rowan Williams

Of all the experiences we have missed during our period of extended lockdown, the slow, shared meals with family and friends to celebrate special occasions must be among the most poignant. This is when good food is prepared with love, and the cares of the normal day are set aside to create a hallowed time of sharing, of being together, of making memories. All this has been denied for - it feels like - forever. Small wonder then that the words of Rowan Williams’ poem awaken a longing in us for those times and occasions to return.

Troitsa, also called The Hospitality of Abraham, Andrei Rublev, 15th century

The icon which the poem refers to is thought to depict the three messengers of God or the three persons of the Trinity, who sat down to eat a meal prepared by Sarah with Abraham. Apart from the preparation of the meal itself, there is an unhurried quality to the story. The visitors are passing by when Abraham presses them to stay. They wait until a meal is prepared, served and eaten with due courtesy and ceremony before providing the final scene to the story which will be played out in a year’s time. It takes time to make a meal, to bake a loaf, to grow a child.

The poem’s time is limitless. It lasts ‘for ever’, the participants rooted in the wood like the figures painted on the icon’s wooden baseboard and eating a bread made from an endless supply of ground beech nuts (beechmast), as freshly baked and essential as local bread is to every feast. This feast, like the heavenly banquet pre-figured in our celebration of the Eucharist, will never come to an end.

During one of our, now regular, conversations regarding symbols of Eucharist with Tom O’Loughlin, Robert Burnett, and Nicholas Postlethwaite, we were reflecting upon the slow symbolic action of bread-making. Nicholas drew our attention to Robert Penn’s history entitled ‘Slow Rise; A Bread Making Adventure’ in which he tells the story of his own attempts to create home-made bread. It is aptly titled because authentic bread making is, we discover, a lengthy labour of love demonstrated by the entire process from choosing and planting the grain, through harvesting, threshing and milling, to the moment of placing it on the table for his family’s recognisably understated response.

He begins his story in Anatolia, Turkey, where the history of bread begins. Local farmer Mahmoud Yulduz, at the end of the morning’s ploughing, invites Penn to eat lunch with him, his wife Sultan, and his son, Tariq. The meal of bulgur wheat, onions, goats cheese, spicy peppers, aubergines and village bread is served with an Eastern courtesy reminiscent of Abraham’s encounter and ends with a promise for the future from Mahmoud, “Maybe you make village bread with your wheat, next year, maybe Mahmoud come in your house to eat lunch.”

Our ingredients are beginning to assemble - Plenty of time, prepared with love, served with courtesy and remembered with a promise. Mahmoud introduces another - Place - ‘your house’. The term ‘Bread’ covers a multitude of different forms specific to their locality, their flour, their conditions, their story. Our hunger for bread is unifying but its realisation is not uniform.

Sadly, Penn’s history records humanity’s amnesia as to the essential value of these ingredients. The work of preparation was increasingly mechanised, speeding up the processes and separating the artisan from the flour production. Fields were enlarged to mammoth proportions and harvested by teams of machines and operatives who moved into the area for this purpose alone and moved on. The local variation was obliterated in the cause of efficiency.

Bread also became a sign of elitism - as removing the bran from freshly-ground flour was costly, only the wealthy could afford a whiter bread. It was politicised creating a pain d’egalite after the French revolution (which the French universally hated) and a National loaf during the World War 2 (which the British universally hated). Even as recently as the Arab Spring uprising one of the rallying calls against dictatorship was for ‘Freedom and Bread’.

Speed, politics, control and despair are poor ingredients for our shared future.

Then he took a loaf of bread, and when he had given thanks, he broke it and gave it to them, saying, “This is my body which is given for you. Do this in remembrance of me.” Luke 22:19

Time set aside, gathered around a table, shared with love, expressed in the courtesy of gratitude and the promise of a memory so significant that the action would be repeated and repeated until all were fed. In this way Jesus presents us with an essential act of such simplicity that it should be impossible to forget , and yet…

Are we, as Church, in danger of moving from the domestic-sized gatherings of the early Church to the volume of the cathedral, where many may gather to receive swiftly and efficiently, providing they meet the strict compliance standards?

Are we in danger of creating an artificial distance between the raw material of our experience from which the flour of our faith is milled and the physical sacramental experience of eating bread?

Are we in danger of eliminating local variations where the celebrations adopt and adapt to the authentic flavour of the community, in fear of impurities entering the mix?

Can we still recall the promise that Jesus would be with us always, in this form, when so much of the essential food has been stripped away?

A change has begun. We are awakening to a different way of living together, but the pressure to return to the familiar will begin all too soon.

We began the history of Bread in Eastern Europe and it is the Eastern Church which may be able to provide a starting point. Tom O’Loughlin reminds us that whilst we interpret Catholic to mean Universal, Katholikos is translated as integral, integrated, with integrity. Applied to the bread of the Eucharist this produces a more nourishing, localised and authentic loaf.

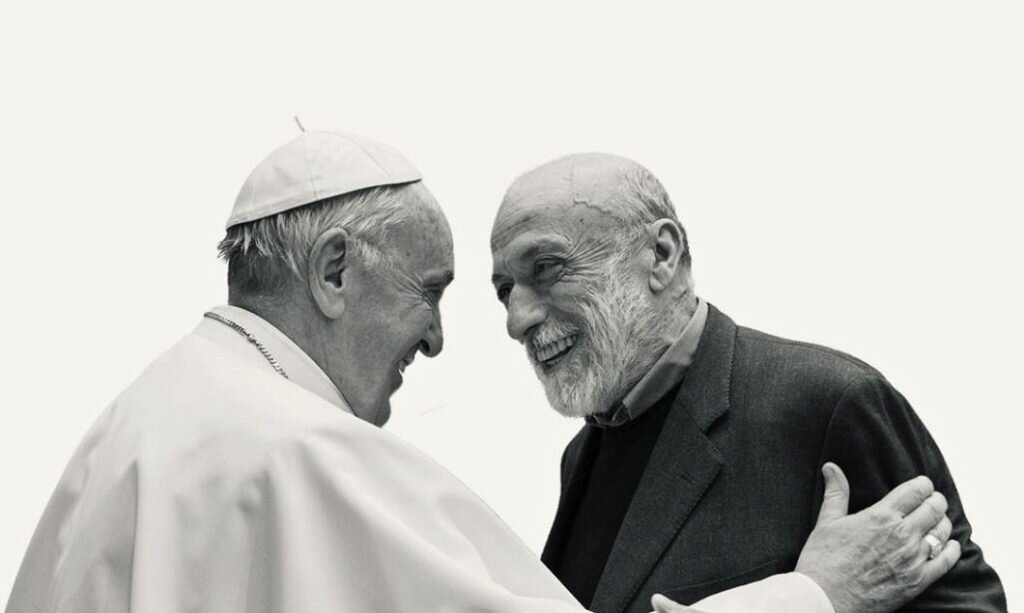

Carlo Petrini meeting Pope Francis

Another signpost can be provided by the slow-food movement which was founded in Italy by the agnostic Carlo Petrini. It makes no sacramental connections but acknowledges all the essential ingredients described above. Recognising that the desire to eat is shared by us all, they aim to ‘reconnect us with the food we eat, where it comes from and how our food choices affect the world around us’. The authenticity of their approach has led to a dialogue between their founder and Pope Francis and a publication entitled “Terrafutura: Dialogues with Pope Francis on Integral Ecology”

In this initiative Pope Francis demonstrates that the integral mix or our Eucharist requires dialogue within and without our immediate community.

Lockdown brings an interruption to normal practice. Some people have seen more of their families rather than less. Some have more time to think, some have never been busier, but it is an interruption, nonetheless, and with an interruption comes altered perception. Could we take the time to love one another better, to listen courteously to the diversity around us, so that we can begin to live Jesus’ promise? Can we sow, grow, harvest, thresh, grind and bake a better Eucharist?

“God knows how weak our memory is so He has done something remarkable: He left us a memorial. He left us Bread in which He is present, alive and true, with all the flavour of his love.”

Pope Francis on Twitter @pontifex